I møte med landskapsmaleren Nils-Aslak Valkeapää

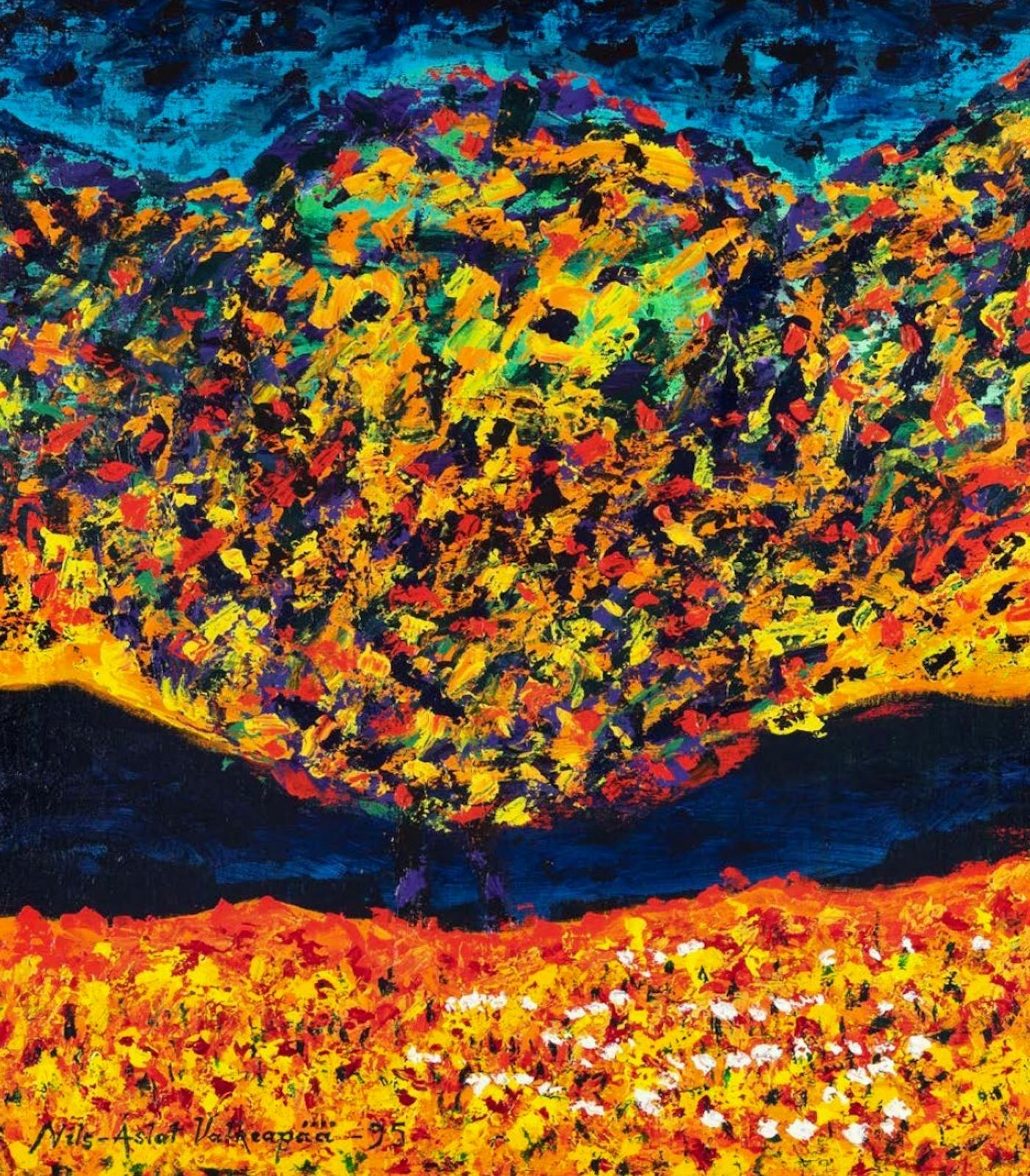

↑ Nils-Aslak Valkeapää / Áillohaš, Nama haga / Uten tittel, 1995.

Photo: Øystein Thorvaldsen / Lásságámmi vuođđudus / The Lásságámmi Foundation.

I møte med landskapsmaleren Nils-Aslak Valkeapää

The sun stands in the west. We are on our way to the opening of the Mohawk artist Shelley Niro’s exhibition at the Riddu Riđđu Festival in Olmmáivággi/Manndalen. I am maintaining good speed. 1,500 kilometers from Oslo. The others sleep as we put behind us the looming mountain region that the Finnish call Käsivarsi (The Arm). The E8 highway stretches out like a silvery-grey ribbon.

It’s almost six o’clock and I am due to give the opening speech at seven. The July evening is cool, the air rich with summer. Rivers, ponds, lakes gleam deep blues, grey scree and rock, birch-green, willow-blanched, reindeer moss, lichen, reddish brown heather, yellow bog grass, pale blue sky. The mountaintops are rounded, not sharp-edged like those along the coast, but softened by glaciers’ caresses over thousands of years. The layer of humus has only just begun to accumulate. Soft windswept peaks give way to fen upon fen and hollows of mountain birch. Here the reindeer paths meander from the pine forests around Guhttás/Kuttainen to the cliffs and grass ledges above Ivguvuotna/Lyngenfjord. The reindeer have taken possession of every fleck of earth. This is the place where the three Nordic nations converge, in the Three-Country Cairn where the pastures are divided by straight borderlines.

We are in the homeland territory of Áillohaš, and just as the Ádjámohkki River twinkles on its winding descent from the northeast, a song drifts into my head. It has a forward-leaning rhythm with push and stop, clip-clop and hop. And when we arrive at the gallery space at the Davvi álbmogiid guovddáš (Center of Northern Peoples) in Olmmáivággi, the opening event is already in full swing. Passing through the doorway, we are met by the same joik that came to my mind a little earlier in the car. Ingá-Máret Gaup-Juuso is performing Áillohaš’s joik called Davás (Northward). The craggy score, with bushes, crooked birch trunks, and echoes of reindeer tracks has beaten us to the punch.

Áillohaš, who like the other Sámi artists that establish themselves in the 1970s, stand on the shoulders of the 20th Century pioneers in Sámi visual arts and handicrafts.

”Walls used to be unknown in the Sami culture, and so nobody hung up pictures.”1 Áillohaš uses the image of the house to depict a view of art and nature in which boundlessness prevails, no restrictions or limitations. Here, the four walls of a house are not a frame, contrasting traditional Sámi tents and turf huts, but rather a square western optic in juxtaposition to the world’s roundness. Modern houses do not make for a worse appearance; and yet, the world appears to be worse. In an era ruled by individualism, indigenous people’s philosophy may represent a possible moderation of the “I”, and in the destruction of the environment caused by industrialism and consumer society, “…teach the world a philosophy of life which could be its salvation.”2

Dwelling in a house must have been vexing for old mountain Sámi people, a limitation akin to walking in hard shoes instead of in soft fur boots, gállohat and waterproof leather skin boots, čázehát. These are people who passed their entire lives living in tents, following the eight seasons, wandered with the reindeer. Consider the hardness of a floor as opposed to a bed of birch branches and reindeer skins. And the trapped air, musty food and rancid dust as opposed to the scent of fresh sweat, dry wood smoke, and the boiling meat over the fire. The aroma of fresh brewed coffee, birch twigs, and reindeer skins acts as a balsam. Toss on a juniper branch and you have crackling music and purifying incense. Within the tent, every undertaking can be restitution.

Laestadian iconoclasm

The smell of camphor lozenges. The hymn is fervently slow-going. The organ’s intonations are not missed at all. The grey painted benches creak. Here there is no décor in through which sin might slip to entwine and muck up the soul. Topping and foppery are traits of debauchery and wantonness. Here there is only reading and the meek waiting of the pups of mercy. I am back in my childhood house of worship, located directly on the opposite side of the river across from the Riddu Riđđu Festival and the Center of Northern Peoples. With its stripped-down interior, the Manndalen house of worship resembles Laestadian gathering houses in other places on the Finnish and Swedish side in the upper parts of the Tornedal region. From the mid 1800s and onward, this was the epicenter of the Laestadian awakening.

I do not know how the Christian religious regimen played out in Áilus’s childhood home, but I assume that Laestadianism characterized his family, as was often the case in our area. This pietistic form of Christianity has, for better or worse, become our faith and the dominating practice of religion, cultural expression, and outlook on life. Joik was of course condemned, as was the reading of worldly literature, dancing, and all forms of amusement. Abstinence, work, and frugality were the primary virtues. Even though love of one’s neighbor and forgiveness were also high on the list, the worldview in Laestadian milieus has primarily been black-and-white, marked by fear and condemnation. “So how can the preachers condemn? They sow fear in the human heart, and create Hell here on Earth.”3 Áillohaš clearly distances himself from such fire-and-brimstone preachers and from the fear-driven notion of god which they put forth. He even calls the work of such preachers terrorism, describing it as devilish with paganistic traits, and wonders if God could truly stand behind such antics.

The experience of this kind of Christian practice must have left a strong impression on the young Áilu, something he continues to carry with him, though without rejecting God. I can picture him accompanying his family and relatives to Laestadian gatherings and to the great yearly Midsummer market that took place in Ivgobahta/Skibotn. The assembly that was held in conjunction with the old marketplace, brought together thousands of Laestadians, and was an important meeting spot for the region. Here, people from vast regions in northern Norway, the fjord areas, the islands, and the mountain villages would come to mingle with others from the Swedish and Finnish inlands. It was here that the preachers admonishingly got with them the masses with their revival cries. I can feel the bubbling atmosphere, old and young together, the warmth, and I hear the slowly-building, almost Kalavala-paced sermons simultaneously interpreted into Sámi, Finnish, and Norwegian.

Fear for the end of days is hammered in with a particular vengeance. The clap of thunder warns of judgement day and the end of the world, but as promised, the raven chicks, tits, swallow fledglings, snow buntings, and nightingales will be provided for by their heavenly parent when the time comes.4 Áillohaš has heard the thunderous sermons, but would like to lift the weight of several centuries of Christianity and take back the Sámi gods. Following the church’s missionary work and battles against spiritual cultural expressions, few Sámi drums are still in existence. Around 100 drums and drum components are scattered in collections, as well as a few depictions of drums that were painted and interpreted in the 1600s and 1700s, which makes them useful sources these days. Of the few remaining drums, and the knowledge of how they are used, a certain understanding now exists about the times when they were put to use on a daily basis.

The Sámi god of thunder, Horagállis or Dearpmis roars—threatens with bad weather, but also secures and provides wellbeing. In many ways, Lars Levi Laestadius’s Christianity is in harmony with the Sámi mythology and language.5 At the same time, the richness and imagery, characterized by metaphors and the use of images from the natural world, was jeopardized by the prohibitions and life-hostile messages of Laestadianism. The sparseness of imagery and renunciation of colorful aspects of life which Christianity represented, functioned as a negative soundboard when the adult Áillohaš opposed his Christian upbringing, desiring to paint a Sámi world saturated in bold colors.

Drawn territory

What had previously been designated as Sámi territory became known, in the first half part of the 1970s, as Sápmi, a modern term and catchphrase for a borderless Sámi region spanning four countries. The pan-Sámi map by Hans Ragnar Mathisen, of which 5,000 copies were printed in 1975, became the iconic representation of this shift.6 Up until this point, Sámi art had—to put it simply—primarily been art in small scale. The art of objects carried on and with one’s self, and in the form of applied arts; clothing, knives, cups, vessels, leather tools, textiles, wood and horns elaborately decorated, ornamented and marked. Throughout the 1970s, a shift of scale took place on multiple levels. Art originally dedicated to a familiar circle is now introduced to a larger audience. The Sámi house marks, muorramearkkat, shall now mark more than ownership of things; they are now also used to mark the entire vast Sápmi region. Áillohaš, who like the other Sámi artists that establish themselves in the 1970s, stand on the shoulders of the 20th Century pioneers in Sámi visual arts and handicrafts, duodji: Johan Turi, Nils Nilsson Skum, Jon Pålsson Fankki, Asa Kitok, John Savio, Per Hætta, Nikolaus Blind, Lars Pirak and Iver Jåks, to name a few of the most well-known. Not to mention the shoulders of the many who sewed, embroidered, applied, braided, wove, twisted, coiled, hewed, notched, sawed, whittled, felted, and scribed as a part of their daily tasks. “But Sami culture is not strange to art. Far from it. Art has been a part of daily life for the Samis, something one doesn’t even talk of in isolation. Real folk art.”7

In the corridors of the health center in Kárášjohka/Karasjok hang four paintings, three of them side by side as a triptych. They stem from 1987, early in Áillohaš’s new period in which he painted large, bold-colored acrylic compositions. The paintings are more scintillating than his earlier or later works, with more layers, painstaking details, and color combinations. Their articulation is more controlled than the expressive midnight sun landscapes from the early 1970s, or the experimental paintings from the Roavvenjárga/Rovaniemi exhibition in 1975. The gestures of a quivering hand remain the same. The summer night light and winter twilight are represented, of course, as are the mountain landscape and deep lakes, and there are multiple perspectives and compositional layers across the three cohesive canvases.

I can see glimpses of predecessors of Sámi art in these paintings; Skum’s landscapes, Turi’s reindeer, and Jåks’s dancing bodies, but also the thoroughness of craftmanship and the precise scribing of the duodji masters such as Fankki, Hætta and Pirak. Áillohaš’s paintings have textile qualities too, as patterns, borders, pieces, stitches, and applications unfold.

And yet, there is a new level here, a new temperature. The stylized figures we recognize from drums and rock art occur as if in a new aggregate state and are actualized, almost singing into this blue-red-yellow-green space. The way in which the figures are spread out, nearly in the familiar landscape in the background, nearly not, creates an intoxicating sense of multidimensionality. The paintings are like tablets, or icons, bearing unreadable script. But for the initiated, they are precise descriptions of correlations between history, the spirit world, and now. And now, Sápmi, the Sámi space, has become habitable and safe. A Sámi nation can be spoken on one’s lips. The notes go unexplained, but it is an apparent manifestation of a history and the right for a people to have a history. This manifestation is solidified with figurative language as well as an intensity, a spirituality, almost in the form of an official declaration: We exist and have existed. We were here before the colonizers from the south. We have a history. “The ancient Romans were already aware that Samiland (Laponia) existed.”8 In spite of the fact that so much has been taken from us and so much has been destroyed, this has been written in stone. Rock art carvings of dancing, drumming peoples near the sea in Alta are 3,800 year-old blessings from our ancestors.9

Indeed, Áillohaš must have felt called, elected, willing, and ready. He appears to have had another and larger project than us other artists, a project concerning time, place, consciousness, and planning. Áillohaš becomes the premier artist of the new Sápmi, endowing his people with common images and colors, just as the petroglyphs in Alta must have appeared to him as a vision of the lost Sámi society. There, the life-giving Sun radiates through people and landscapes, connecting us with the heavenly spheres and subterranean lakes, animals, gods, and spiritual beings. With alters and rhythmic dancers as intermediaries. These paintings act as new atlases and maps. The new-rock-carvings10 both depict and actualize this geography, and help to redefine and liberate the very bedrock itself. It is Sámi imagery which redefines and puts ethnic colors to the rock art and the bare-rock face at Alta which is listed as a World Heritage site. The series of paintings from the end of the 1980s and onward also acts as weapon and shield in a new arsenal of Sámi art. The paintings ally the Sámis with other indigenous peoples throughout the world, with the San peoples’ cave drawings of hunting scenes at the Cape of Good Hope, with the handprints of Fuegians on the cliff walls at Bahia Yendegaia, Magallanes, and those of the Aborigine peoples in Gariwerd, Victoria.

The Bird Man

The birds keep coming back in the paintings of Áillohaš. When I look through the bird books I have on my shelf, I cannot find the high-flying duckbirds from the painting over the fireplace in Lásságámmi from 1975, the ones with blue wing feathers and green, yellow, and red on their chest. Nor can I find the yellow-legged birds with glittery feathers at their back ends from the health center in Kárášjohka, nor the pussybird with five legs planted in the snow which now hangs in a home in Romsa/Tromsø. It’s possible I saw a similar creature once in a snowdrift outside of Saskatoon, or in the morning mist up at 18,500 feet on Kala Patthar, but never in the Nordic fauna. These are not like gulls, skávhlit which can be found everywhere, or the swan njukča, that comes when the channels through the ice open up, or the black-throated divers, dovtta which complainingly shriek by the waters on spring evenings. These are not hurri, black grouse, giron, ptarmigans, gáranas, ravens, bižus, golden plovers, or hávda, common eiders. These birds must have come from dreams and visions, from other worlds. Because these birds are not quite earthly, there where they hover between heaven and earth. Perhaps they are harbingers, messengers, true angels and helpers. Or perhaps they are nemesis and birds of ill omen, guoržžu. Áillohaš said he spoke with the birds and self-identified with the love-longing, sun-seeking beautiful little bluethroat, biellocizáš11 12, jewel of the birch forest with a voice like a bell.

The Signature Nils-Aslak Valkeapää

Áillohaš’s figures are often roughly, recklessly painted, though in other forms of expression he is meticulous. It’s as if his goal is not to achieve a technical brilliance, but rather a hurried, unschooled—if I dare say—vernacular expression. A naïve, rudimentary style. Something stemming from a tradition different than European art history. As if the gestures are based on the belief that they must be properly implemented, that they are in alliance with a greater meaning. The painting is merely a registration, traces of corresponding rituals surrounding the canvases. In many of the paintings, the figures are retaliating, they appear in formations, and they burn fires that are ablaze inside the paintings. And the paintings keep on coming, and the reindeer swim out to their summer habitats on the islands. In the warmest of the paintings, one can undress and have sex in the open. Among the coolest, it’s key to be properly dressed. Love here comes through nonhuman relations, or in a love for all, for everyone and everything. For Mother Earth, Máttaráhkká, Pachamama, Gaia, Holy Mary. For all things wet and dry. For the ocean. For the mountains. For Sápmi. Áillohaš signs this. He signs with Nils-Aslak Valkeapää written large. Signs beneath the midnight sun and the dwarf birch, skierri. With a signature that is one and a half feet wide. He writes beneath the land. In the vegetation. His early signatures are loose and easy, while later ones are painstakingly applied to the paintings and images in bold red and chartreuse neon colors. Among the most striking of Áillohaš’s works that we have been given, are a series of owls fashioned from flat stones. At first glance they look like ordinary mountain stones with lichen and signature. But then, suddenly, the stones pierce you with their eyes. Just as skuolfi, the owl tends to do.

Photo: Øystein Thorvaldsen / Lásságámmi vuođđudus / The Lásságámmi Foundation.

Photo: Øystein Thorvaldsen / Lásságámmi vuođđudus / The Lásságámmi Foundation.

The spots that look like orange-yellow lichen are in fact paint that serve to animate the stones. “Sami art is part of the philosophy of life. So it is something which goes together with the countryside, harmonizes with and echoes it, without leaving a mark behind.”13 It’s as if Áillohaš wishes to emphasize this with his late output. Many of the works could simply be what they are: stones, gravel, boards, bits of wood, worm-eaten fragments. But he has modified them somewhat and then applied his signature. When we think of his early field recordings, his sound recordings of nature and environment, of reindeer migrations, bonfires, dogs, birds, and his practice of record-keeping and typological photography over the decades, one naturally thinks of a context and a readymade-approach to the material. Of course, references to art historical Dada and pop art, with flamboyant artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Raoul Hausmann, Meret Oppenheim, Andy Warhol, or Claes Oldenberg, don’t exactly fit in with the art of Nordic indigenous people. The designation objet trouvé (found object) is thus better in this context, as it may signify more nature, storytelling, and the original qualities inherent in the materials. The term is less urban and is able to bear the weight of a more complex concept and poetic treatment. Áillohaš places his signature on that which—more or less—nature is doing, and depicts a small fragment, a cross-section, of this process. As proof that everything is one. It is.

Out into mythical landscapes

If you venture out into Sámi landscapes, you will eventually come across Áhkká (The Wife), Gállá (The Old Man) or Áddjá (The Grandfather). And you will come across Luossaipmil (The Salmon God), Ceavccageađgi (The Fish Liver Oil Stone), Bálddesgeađgi (The Halibut Stone), Tjåehkere (God Mountain Island) and Gálddo (Spring Bottom). The names and places might bear witness of understanding, order, and ritualistic circumstances to points embedded in the landscape. They signify a correlation between humans and their physical surroundings, that some places are well suited for sacrifice, healing, or other ritual use. One may find that it helps to offer a coin, antlers, or a little cod liver oil in order to receive fortune in reindeer herding or fishing, or good weather on the journey. And how could it not be beneficial to sip straight from a fresh, crystal-clear wellspring?

The places are there like markers and reference points, as reminders of the correlations that truly matter, and of the subordinate position of humans. The landscape is inhabited by powers, creatures, and gods invisible to the ordinary naked eye. It is a mythical landscape14 that might explain the origins of the world. It is a physical manifestation of events that occurred in times past, and myths played out in the starry sky, reflected back on the earth’s surface below.15

Sieidi, the widespread Sámi word for sacred places, refers specifically to special rock formations, but also to other larger or smaller cult locations that have magical qualities about them, as well as stories that have been handed down through time. Such locations function as meeting spots for communication and as a link between us and the afterlife.16 A glance at the map shows place names like Sieidegieddi, Sieiddirášša, and Sieidaš in several linguistic variations and compositions across the entire Sámi region from east to west, north to south.

The sieidi formations might well be considered the most outstanding exemplars of Sámi sculpture. They have arisen “on their own”, are a part of the landscape, and hold significance for many. Offerings make sacred the simple acts of humans and the materials cross over into other dimensions. What happens to a piece of meat offered at a sieidi up in the mountains? I ask myself too, whether a human being can be a sieidi and whether the sieidis can have a place in the media, in a virtual landscape, and among algorithms. Sieidi is tied to language and its meta realities.

Indigenous perspectives, and the correlations and interdependency between humans and our natural surroundings, have been urged, also with strong words and activism.

The Sun, our father, The Earth, our mother

To sign one’s name on the unwritten laws of nature—the laws of life—may be done with a light touch. We stand today facing a climate and environment crisis, of which we can only guess the contours, and which impacts us all. “Today the world has come so close to catastrophe that we have every reason to blame ‘advanced culture’ for being the greatest danger in world history for ‘underdevelopment’.”17 Áillohaš, and many with him, warned about this crisis several decades ago. Indigenous perspectives, and the correlations and interdependency between humans and our natural surroundings, have been urged, also with strong words and activism. We are one. But the message does not appear to be getting through. Nations, courts, and industries bang on the table with treaties, laws, and contracts. “my sisters, my brothers, they too, here too.”(ny footnote kommer)18 Indigenous philosophy can feel too romantic, coquettish and naïve when the largest industries in the world are the exploitation of natural resources, energy, weapons, and not the least, finance, property, tourism, drugs, and information. We are permeated by, addicted to, and enslaved by the kingdoms of Apple, Google, and Amazon. I often ask myself how we as Sámi indigenous peoples, might be able to offer up a “philosophy of life which could be its salvation”, how the message could possibly get across? Indigenous peoples all over the world are currently battling for land, for their values and future. This demands defense and temperance, but also the recognition that spirituality and art often don’t strike the same chords as ethnopolitics. The same sentimentality that is used to signify a people, a group that shares a common background and characteristics, may also be used to wield brutality, exclusion, and abuse. Ethnopolitics can therefore overshadow and repudiate the decisive battle for the environment and climate, which is of utmost importance and concern for us all. It is here that indigenous philosophies might be able to contribute with alternate ways of thinking, alternate economies, and particularly by offering the possibility of a different set of life values—different kinds of dreams.

With the release of Eanni, eannážan (The Earth, My Mother) in 2001, Áillohaš ends his almost thirty-year-long artistic oeuvre with artists books—art in the shape of books. Eanni, eannážan spans the globe and includes photographs of indigenous peoples in South and North America, Greenland, Africa, and Asia, but starts and ends in Sápmi with Áillohaš’s own photographs and paintings. The text begins in the clouds, wanders out into the world, conveys a message that is unifying, informative, and eco-friendly, and ends back in Olmmáivággi, Áhkkávággi/Kjerringdalen and Nieidagorži/Pikefossen, caressed by the Sun, cradled by the Earth.

Beaivvi, áhčážan (The Sun, My Father) from 1988 marks, for many including myself, a milestone of a book and an awareness of a greater Sámi community. While Eanni, eannážan spreads outward into the world and the world’s reality, Beaivvi, áhčážan moves within a smaller, more intimate Sámi circle. The book, with images and poems, is reminiscent to a greater extent of a mythical realm, a story of origins, of the lives of foremothers and fathers, and of a common Sámi landscape. I can recall the first time I saw the book; it was in my cousin Lars’s flat in Romsa. I remember the spring light and the view toward Sálašoaivi/Tinden in Tromsdalen and the grooves in the faces, like cracked hills, of lives lived, weather and wind, eyes scorched by smoke and broad vistas. The old photo technique and silver nitrate highlights the eyes, the inner radiance, and details. The oldest portraits, from the 1880s, are so intense that the old Sámis seem to be gazing directly at you more than one hundred years later. They are marked by a life lived outdoors, presence, and their skills of observation. One gets a sense of what has been lost, the bygone days of one’s own modern, middle-of-the-road life. Of course, you long to escape the 9-to-5 grind, the empty cycle of consumption when faced with the good, free life lived amongst the reindeer, on the move, in the lávvu19, in the goahti20, in your siida21. With open gazes, they invite you in. They are groups and families, many of whom have genealogical traits recognizable in people you have met before. And most likely some that we ourselves are related to. Those who before moved between the inland and the coast, who took up residence in our home valley. Áillohaš also includes his own relatives in the collection. Those from Geagganvuopmi to Stuorranjárga and Ittunjárga. He has also snuck in two set photographs of himself, taken by makeup-artist Siw Järbyn during shooting of the film Ofelaš (Pathfinder) in 1987.

The work of Beaivvi, áhčážan is a staging of archival material and an artistic treatment of existing photographs from collections around the Nordic countries, the USA and Europe. The scope of the body of work is a testament to vigorous research and to the negotiations doubtless required to use the material in the book. The use of the photographs also interacts with the motivations behind the camera. Most of the photos were taken by non-Sámis for ethnographic research purposes, and some of them are material taken from racial biology research. But Áillohaš does not shy away from the evil motivations behind some of the images, namely the intent to portray Sámis as subhuman. But the important thing was now to show the historical testimonies and portraits, and to return the photos from the collections back to the Sámi peoples, to take back dignity, and to visually depict the history of Sámis. Those pictured are heroes, perhaps not in the midst of battle but people at work in the landscape and in various stages of life. The images are widespread in their geographical origins and cover the entirety of the Sámi region: from Peäccam and Kola Peninsula (oversettelse kommer) in the east to Viesterála in the west, from Finnmárku in the north to Trööndelage and Herjedaelie in the south. There is no shortage of problematic photographs, such as the prisoner photos from Oslo after the Guovdageaidnu/Kautokeino uprising of 1852, Sámis on display in Germany and France, images of forcibly displaced Sámis in Sweden, and the typical post-card compositions that can be found at the souvenir kiosks. Even Sámi participation in polar expeditions and reindeer husbandry projects in the USA have been given a place in Beaivvi, áhčážan. The composite narrative not only shows pictures of a tough way of life—survival, Sámi life, friendship and fate—but also deals with the hurt and pain of having the photos taken in the first place. In this way, the book is emancipating contemporary art. In a sense, it allows the faces, bodies, and groups to lighten their own historical yoke.

The reindeer are a constant theme throughout the book, directly as a form of livelihood, or as a symbol of power, and also as mythical creatures. Reindeer provide meat, milk, skins, bones, innards, and antlers, and can also be harnessed for transportation. With its alpine habitat, appearance, and movement through the landscape, the reindeer has been an icon of northern survival for thousands of years. In Beaivvi, áhčážan, Áillohaš allows the reindeer to form the poetic cycle through the use of typography.22 23 Like a stream of animals, the reindeer moves soundly through the text. While Eanni, eannážan has a global and ecological base motive behind it, Beaivvi, áhčážan tends toward the mythological. We hear the reindeer and birds, but also the voices of our forefathers and mothers calling us across a timeless, mythical origin, a dream time, a drum time. Together, the two books can form a single organic unit. Sápmi is in the world, the world is in Sápmi. And we must find ways to practice solidarity.

It can be stated that Beaivvi, áhčážan is a Sámi national epic24, with the book’s pathos and emphasis on the past, origins, unity, pride, and heroism. The Sámi people are indeed children of the Sun, but what I find truly epic about Beaivvi, áhčážan is the radiance of the individual human being—as a part of nature. Áillohaš incorporates a circular perspective that may serve to counteract the static, the final, the original. It is an ecology, an antidote to the ethnocentrism that lurks in any widespread community project. The book ends where it begins, in physical history, in a landscape, with sieidi, birth, death, drums, stones, human being.

- The essay is part of the publication Nils-Aslak Valkeapää / Áillohaš published in print in conjunction to the exhibition Høvikodden: HOK/NNKM, 2020

- Nils-Aslak Valkeapää/Áillohaš October 23, 2020 - January 10, 2021

- Henie Onstad Kunstsenter Main Gallery

References

-

Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, Helsing frå Sameland

(Oslo: Pax Forlag, 1979) p. 63

-

ibid. p. 127

-

ibid. p. 70

-

Roald E. Kristiansen, Lars Levi Læstadius, www.kvenskinstitutt.no

-

Lars Levi Læstadius, Fragmenter i Lappska Mythologien. Gudalära (Tromsø: Angelica Forlag, 2003)

-

Hans Ragnar Mathisen, How it all started, my first maps, www.keviselie-hansragnarmathis...

-

Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, Helsing frå Sameland

(Oslo: Pax Forlag, 1979) p. 63

-

ibid. p. 23

-

Irene Snarby, Multikunstneren Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, www.lassagammi.no

-

Knut Godø, «Ailo helleristeren,» Harstad Tidende, unknow date, 1991.

-

Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, Helsing frå Sameland

(Oslo: Pax Forlag, 1979) p. 126

-

Náste-Gáisi, Om du også hadde vært Biello-Cizáš, kunne vi kvitret sammen om morgenen. Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, Vindens veier. Translated byLaila Stien. (Oslo: Tiden, 1990) p. 166

-

Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, Helsing frå Sameland (Oslo: Pax Forlag, 1979) p. 63

-

Arvid Sveen og Håkan Rydving, Mytisk landskap (Stamsund: Orkana forlag, 2003)

-

Jelena Sergejeva (nå Porsanger), Nokre samiske stjernebilete: Eit jaktfolks forestillingar om stjernehimmelen, Almanakk for Norge (Oslo: Universitetet i Oslo, 2001)

-

Johan Turi, Samene og noaidikunsten (Tre bjørner forlag, 2014)

-

Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, Helsing frå Sameland

(Oslo: Pax Forlag, 1979) p. 126

-

Nils-Aslak Valkeapää, Jorda, min mor (Kautekeino: DAT, 2006) p. 118

-

The reindeer herding tent for traveling

-

Gamme or tent with arched pole construction

-

Community in reindeer husbandry, camp, hamlet, farm, home

-

Harald Gaski, En vandrende reinflokk på papir, www.lassagammi.no

-

Sigbjørn Skåden, In the Pendulum’s Embrace, in Nils-Aslak Valkeapää / Áillohaš (Høvikodden: HOK/NNKM, 2020), p. 51

-

Kari Sallamaa, Beaivvi, Áhčážan – samernas nationalepos, www.lassagammi.no