Happy

Happy

By Bjarne Melgaard

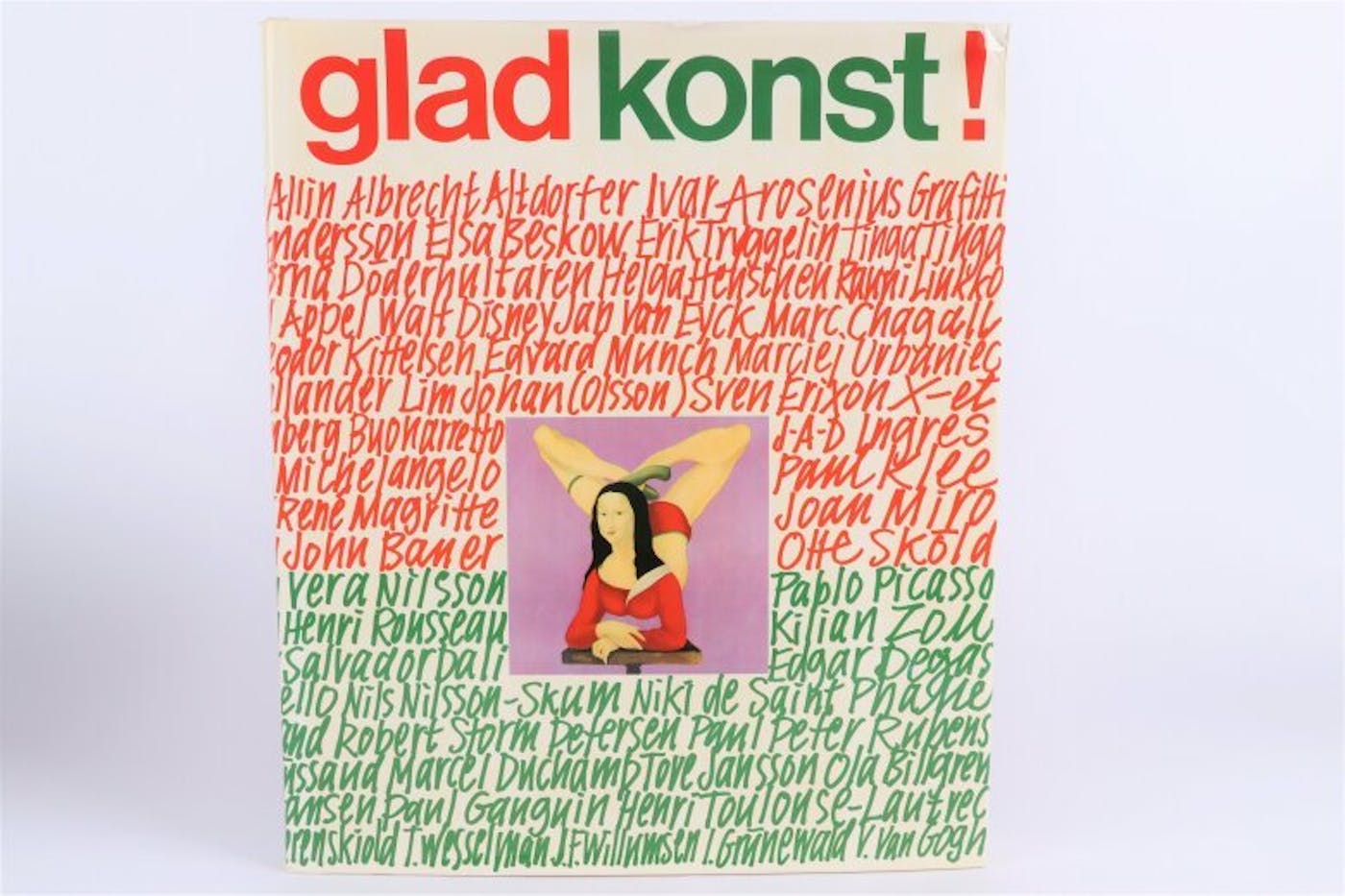

I tried googling Happy (Glad), a book from the happy Swedish 80s, the book where I first saw a work by Niki de Saint Phalle, but I gave up in the end. It seemed nearly impossible to locate. A bit like my relationship to her… The lost treasure Happy was a survey of just that: happy art. And in many ways, that is what Niki de Saint Phalle has been associated with most. Everything from big, fat, cheery female figures that sort of strut or prance around in fountains or garden sculptures, to perfumes and fashion, full of energy and joie de vivre.

I was given a copy of Happy by my mother and fathers’ Swedish friend, Britta, who we got to know on a camping holiday in Sweden. The book covered everything from how Swedish subway stations had been decorated by various Swedish artists, to how one ought to maneuver through the new experience of a trip on the subway. It also presented the art of Siri Derkert and Vera Nilsson and their efforts to promote art in the subways, considering that the average Swedish citizen spent about four years of his/her life in subway stations, according to a statistic from 1950. During the 1970s, Trafikens Kunst Næmd, which had established a committee, noticeably radicalized subway decoration and the result is that Sweden today has some of the most experimental subway stations in Europe.

But so, getting back to Happy and my first encounter with Niki de Saint Phalle’s art. First of all, there was the picture of a gleeful, curvy Nana. This was her signature form and in many ways set the benchmark for how her art has been judged. But if there’s one thing I have never much been, it’s happy. So it’s paradoxical that I first saw Niki’s art in a book about art’s amazing ability to draw us out of the deepest depths of misery and into a landscape of infinite euphoria.

But what the book Happy managed to do, in a simple and straightforward way, was put Niki de Saint Phalle in perspective to Sweden, and especially during Moderna Museet’s heyday, when Pontus Hultén was director. In 1966, she created the monumental work She – A Cathedral, which was one of several projects Pontus Hultén realized in addition to other groundbreaking works and installations with artists like Paul Thek, for example, and many others. This was a time when museum directors were visionary and to a great extent directly involved in executing new artworks for their museums and exhibitions; this is what made it possible for Niki de Saint Phalle to realize She – A Cathedral and for Paul Thek to create his large-scale installation Pyramid, A Work in Progress between 1971 and 1972.

But I assume this exhibition and its catalog will be overflowing with all manner of chronologies, dates, works, and reproductions, so I would rather concentrate on some other references I have to Niki de Saint Phalle than just historical rhetoric: the rather less cheery and confident sides of her art. And some rather more obscure reflections around her position, and specifically references to the concept of the female body as well as the concept of the female.

Photo: Ⓒ Hans Hammarskiöld Heritage

After Britta from our camping trip in Sweden in the early 80s (or late 70s) gave me the book Happy and made me aware of Niki de Saint Phalle, mama and papa had a falling out with her because they didn’t like how she’d constantly turn up in Oslo (along with an exceptionally charmless daughter) to pay a visit and almost always empty the kitchen cupboards of everything they had to satisfy a seemingly insatiable appetite for Norwegian ham and cheese. But regardless, Britta is to be acknowledged for having been the very first to make me aware that Niki de Saint Phalle existed and that one could be happy even though one never was, and that one could read about Nanas and Swedish subway stations and still keep one’s chin up. And like everyone else, I had the impression that her art was about stimulating a relentlessly uplifting passion for life and boundless creativity in the different projects she did, something I eventually began to doubt more and more. I saw her “shooting pictures” (Tirs) when mama and I went to London for the first time, when I was around eleven years old. We visited the museums in London, like Tate Modern before it became the airplane hangar concoction of a museum that it is now, back when it was a museum that included both insiders and outsiders of British and European art.

So it was on one of these rounds that I saw my first Niki de Saint Phalle work. I puzzled over the slightly dirty and odd work that I gradually, struggling to read the information next to the painting, came to understand she had made by first stuffing various materials into the picture and then shooting at it with a rifle, so that the contents spilled out and left gunshot wounds on the surface itself. She would later describe this as having been a way of shooting herself free from her father’s abuse and rape of her when she was eleven years old. She only clearly articulated this in her book, Mon secret (My Secret), which was published when she was sixty-four.

So right then and there one got the sense that there was more to her than gigantic rotund female forms and an endless, slightly monotonous artistic output. Where did I place her then, as an eleven year old at the Tate in London, and how did I put her into perspective later in life when both she and I had acquired more bullet wounds than one could count? Where did this instinctive desire to react to everything in the world with destruction and decimation come from?

After mulling over what I might write about Niki de Saint Phalle that the catalog wouldn’t cover, I first had to look closer at two elements that I discovered and have thought a lot about in retrospect when it comes to her style, namely weapons and targets. Looking at everything from She – A Cathedral to the Nanas to designers who emulate her, it’s as though everyone has overlooked something essential but actually not so difficult to see if they want to—the fact that all the figures and sculptures are painted with the same round form that the average target has. It is a circle that spins outward, where it is possible to hit the target for the most part right in the bullseye of these circular images.

This is where I want to begin when it comes to Niki de Saint Phalle—the Niki de Saint Phalle I first met through Swedish Britta who gave me the book Happy, and the Niki de Saint Phalle I rediscovered through French female filmmakers like Catherine Breillat and Virginie Despentes nearly thirty years later—with this gaping open wound of a vagina, a target that you can either hit straight on or just stroll around in (not that it’s made any more pleasurable for that reason) and that has a quite specific French tradition, for example with Virginie Despentes’s novel and film Baise-Moi (2000) which presaged our era’s budding female preference to shoot one’s assailant rather than go through therapy in order to move on.

Only a bullet hole could help these women move on. Far removed from a French literary and cultural tradition where women to a great extent were well-articulated extras rather than fully-fledged participants in their own catastrophes. This is the landscape that Niki de Saint Phalle operates in. And as a forerunner to Baise-Moi, French revenge literature, and Catherine Breillat’s films about how abuse and assault blend together like invisible opponents, which in the end are even more disconcerting than the potential assaults. Niki de Saint Phalle pursued this in film as well, with Daddy (1972), which was a direct critique of heteronormative family constructs, and which was harshly criticized by her own family. This is something she has in common with both Despentes and Breillat who, in their own films and novels, tend to put the family under attack and recognize that this institution is the first nail in the coffin, for both men and women, that it inevitably always comes in the way of them finding their own individual voice. A voice Saint Phalle experienced just as much difficulty in pursuing.

In this sense, Niki de Saint Phalle also has a lot in common with the Swedish national icon Marie-Louise Ekman. Ekman began as a model, and she had no problem presenting herself as completely uninhibited by the patriarchy’s dominance, deliberately playing on appearance and stagings of her own “I,” as in the film Hello Baby (1976). Niki de Saint Phalle also supported herself as a model before choosing to become an artist. She was discovered on the street by a modeling agent when she was seventeen, and four months later was on her first Vogue cover. Both women had a similarly easy rapport with the press and other media when it came to promoting themselves in a male-dominated art world, which they both also finessed by marrying famous male contemporary artists. Marie-Louise Ekman started off with Johan Bergenstråhle and ended up with Gösta Ekman. Niki de Saint Phalle married Jean Tinguely who at his best was, well, perhaps more bargain basement Alexander Calder than a particularly autonomous artist. But would de Saint Phalle have wanted an equal partner, one who might have drained more of her than her mental health, institutionalization, and incest already had?

© 2022 Niki Charitable Art Foundation, All rights reserved.

In 2000, Virginie Despentes’s film Baise-Moi created a scandal, with the main character taking revenge against a group of men who gang raped another of the film’s protagonists. The poster for the film is also interesting; it shows the lead actress, porn star Karen Lancaume, standing with a loaded pistol, ready to blow away yet another set of useless, violent, heterosexual men who can’t seem to understand that rape just isn’t funny. But this is where the tables are turned, and suddenly the victim is having fun. Fun in slowly but surely being able to eliminate all her abusers by just shooting them. In the most violent way possible. I think there is a certain logic in men who believe that women find violence arousing, in the end being forced to stare down the barrel of a gun themselves, a hole like the one they’d thought, moments before, they could penetrate without any serious consequences.

Without dwelling more on the motive for these women having such an extraordinary relationship to firearms and revenge, rage and murder, it is interesting to observe that these French filmmakers and authors, such as Despentes and especially Breillat, insist on be able to define for themselves their relationship to their own body and its materiality, regardless of what or how that may be.

But here is where things get more complicated. Niki de Saint Phalle was never very overt about the origins of her rage, or remotely close to Despentes’s punk aesthetic or the mechanics of violence that Catherine Breillat describes in her films. But if one dives deep enough into certain details in de Saint Phalle’s world, one begins to suddenly notice, for example, that in a drawing from 1968 she wrote: “I had to take my diet pills … gained five pounds today around the hips.” And on one of the Nana drawings she wrote: “Will you still love me when I look like this?” I won’t speculate about how much access de Saint Phalle had back in the 60s to various amphetamine-laced diet pills, but as someone used to say to me ad nauseam, “everything is in the details.” There is something about seeing these hints of another version of her than just the ambitious artist struggling to maintain her own relevance in a France that, by the 1970s, was becoming more and more dominated by women like those in Catherine Breillat’s film A Real Young Girl (1976), for example, which was censored and banned before finally opening, to scandal, in 1999. Or Béatrice Dalle, who in the film Inside (2007) breaks into a bourgeois French suburban home while demonstrators storm through the center of Paris. Meanwhile Dalle sits in the house and waits for a man she quickly does away with, after having tormented a pregnant woman in every imaginable and unimaginable way, in the end killing her and cutting the baby out, a baby Dalle believes she has a certain right to since her own pregnancy ended in miscarriage after a car accident.

Well, what all this has to do with Niki de Saint Phalle is maybe beginning to be a bit speculative, but it’s not entirely without reason that I mention that Niki de Saint Phalle wasn’t the only woman in French cultural life that preferred a rifle to dialogue. And this brings me to de Saint Phalle’s cinematic contemporaries, namely author and filmmaker Catherine Breillat, who became a pariah of French cinema with films like Romance (1999), the first mainstream film to show an erection on screen. She also gave porn star Rocco Siffredi his fifteen minutes of fame in 2004 with the arthouse film Anatomy of Hell, in which the protagonists have sex with a rusty garden rake and drink menstrual blood. I suppose my point is that others assumed the mantle after de Saint Phalle’s explosive shooting sprees that ruptured canvases and left their various polychrome contents and spray cans running down them, as if she was saying, like Breillat thirty years later, “I just love blood,” a detail that all of these women have in common.

As I began this so-called essay (suppose it’s moved beyond that concept now…), I would rather try to articulate something about Niki de Saint Phalle and French culture and violence, a construct French art is overflowing with. But in de Saint Phalle there was in the end more violence in the megalomaniacal parks and sculptures she worked obsessively to realize, as if she thought that if the world didn’t get yet another Nana or yet another sculpture with a gaping bullet hole, the impulse to violence would cease. As if she was camouflaging the idea that lively, voluptuous, carefree female creatures could overcome all the difficulties she and countless others worked relentlessly to find a form of logic in, and that this would make her artistic efforts more meaningful.

Because at the end of the day the question is: How many Nanas and optical collaborations with Tinguely can one really take? This seemingly endless creativity had to be a projection of something else. Something one would maybe prefer to keep at a distance? In fact, she describes this in her book Mon Secret, but isn’t it also a way of suppressing the desire to just execute someone, finish them off, eradicate them, as she herself talks about in interviews from the 70s and 80s?

About destruction as the engine of all creative activity and basic survival, where violence is more a condition one slowly becomes accustomed to and eventually finds its expression in a tremendous output of sculptures, drawings, and paintings, and attains something almost overbearing in its ability to seem like it can overcome everything. Even our still-bleeding bullet wounds?

Catherine Breillat’s film Abuse of Weakness was released in 2013, and at that time I was living in New York and had long been curious about the seemingly endless stream of violence and depictions of rape coming from French filmmakers and authors. Gaspar Noé’s film Irreversible (2002) with Monica Bellucci, which includes one of French cinema’s longest rape scenes (and most violent), can unquestionably be included here.

Well, but back to Abuse Of Weakness, the film I in many ways have identified most with, even though on the surface there are no similarities between its main character and myself. This is Breillat’s most autobiographical film. It portrays how, after a stroke, she began a professional and personal relationship with Christophe Rocancourt whom she considered pairing with Naomi Campbell in Bad Love, a film adaptation of her novella of the same name. Bad Love was never produced, but over the course of eighteen months, Rocancourt swindled Breillat out of 800,000 euros, which was meant as a “loan” in exchange for his time and company. What she paid for was the illusion that enabled her to believe he actually felt something for her, although he explicitly expressed on film and privately that he never did. After having woken up in the middle of the night and seen him on TV, she contacted him to ask if he would act in her film, and the film documents her at times incomprehensible attempts to have a relationship with a man who, when all is said and done, despises her, and will not see her without being paid for it, which finally leads to her becoming homeless. To cut a long story short, the film ends with Breillat surrounded by family members, all of whom, without exception, had been absent when she was trying to recover from a stroke and a relationship to a man who took her for everything she had. When these family members ask “why?” she answers that “it’s as if it wasn’t me,” as if cultivating a relationship was what, in the end, cleared her of all her worldly possessions, but also as if her pride and obviously boundless naiveté were things she did not actively participate in.

This is so far removed from the female roles in French film and culture I described previously, where a rifle is just a reach away as an alternative to cultivating a relationship with one’s assailant. But to what extent was Rocancourt an abuser? No one forced Breillat to hand over everything she owned to the man because he was the only one who paid her any form of attention on a film project where interest had been waning (Naomi Campbell withdrew from the project) and she ended up alone and humiliated.

Fast forward, and I am in my own relationship with someone, a twenty-two year old whom I also pay to feign interest in me, beyond the financial. It is 2015, and I am opening an exhibition, “The Casual Pleasure of Disappointment,” at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in Paris. The theme of the show is (no great surprise here...) Catherine Breillat’s film Abuse of Weakness and the socioeconomic relationships that underlay choosing partners that have only contempt for you or see you as a walking bank account that needs constant topping up to avoid even more humiliating truths about the fact that you are actually paying someone to be with you. That your relationship is a financial transaction that both of you have to engage in for it to exist, as Breillat describes so well in her film.

To those who are reading this, the question might be: What does this have to do with Niki de Saint Phalle? Well, a lot. It was the last time I went on any kind of family trip, before papa died, before mama sued me, and we’d decided to spend some days in Paris after the opening. The same opening where I finally met Breillat who, in broken English, told me “there is no sophistication in fraud.” Considering that, the day after, I found myself outside the Pompidou Centre with a family member who would later sue me, a father who would soon be dead, and a relationship to a twenty-two year old that on average cost me between ten to fifteen thousand American dollars a month, I gave a lot of consideration to what Breillat said to me at that glamourous party at home in Ropac’s apartment—“there is no sophistication in fraud”—as I sat down and stared straight at Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely’s iconic work, Stravinsky Fountain, by Place Stravinsky, just next to the Pompidou Centre. The work, from 1983, seemed almost to mock my situation, colored by deceit and a lack of self-respect and the illusion that the family is an institution of love. I began almost to blame Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely’s actually rather mediocre fountain for contributing to the feeling that everyone in this public setting outside the Pompidou Centre with a gang of partners and family, except for my father, had nothing but contempt for me.

I saw the perpetually happy Nana statues as culminating in Niki de Saint Phalle’s own distorted relationship to her own body, rather than in an expression of energy and joy. Something else also came to the surface here, namely de Saint Phalle’s illustrative relationship to voluptuous female bodies; is it a tribute to or envy over these women’s obviously relaxed relationship to their own bodies? And the encounter with Breillat the night before, which also destroyed any tiny illusions I might still have had that we all get the partner we deserve? Breillat also made a film called Fat Girl (2001). The Criterion Collection describes it in the following way: “It’s a simple story featuring a girl who is fat [and who is raped], not the exploitative tragedy we always assume comes with being fat.” It also led to an increasingly more strained relationship to my own weight and to a partner who needed financial incentives for not discussing how my appearance had deteriorated in the two-year period we had been together.

This is where both Breillat and Niki de Saint Phalle are onto something essential. Isn’t the body we inhabit, and also behold, just a hoax? That actually nothing is filled with either vitality or creativity, but is instead a culmination of all this violence one, in the end, has no idea what to do with? As if the eccentric figures at Place Stravinsky are actually only meant to mock our presumption that life is something that gives something back. If we just create enough, the rape, gaping bullet holes, disdain of those around us will all disappear, and we’ll be able to find a kind of logic in art.

At the hotel later that evening, after we’d slogged our way through yet another day with an endless parade of French art I actually loathe (like Arman, Tinguely, Spoerri, and others from the Nouveau réalisme group that de Saint Phalle was the only female member of), my twenty-two year old partner asked: “Are you aware that I just despise you? I hate your stupid show and that old bitch Breillat.” And for one reason or another, I answered with a monotone “yes.” Breillat, in her film, describes contempt as the essence of the fact that every relationship consists of financial transactions to be able to keep things going.

So finally, where does Niki de Saint Phalle end up in my egocentric text about her? Is she the observer of the infinitely pathetic ways we choose to maneuver through our relationships, which we are simultaneously victims of and active participants in? Are her targets and dripping “shooting pictures” part of the origin of what would later be the wave of pure violence in French cultural life? Do we, myself included, want her to be, as she was presented in the book Happy, a standard-bearer for passion for life and creative energy and feminine values, instead of a distorted image of those same values?

In New York the following year, a friend of mine, quite coincidentally, gave me a Niki de Saint Phalle book and said “looks like you could use some happiness,” as if the entire downfall of what had been my life in New York was stamped on my forehead—

where the money ran out, the partner disappeared—and that same spring ended with my mounting the exhibition “Daddies Like You Don’t Grow On Palm Trees” at the Sammlung Friedrichshof in Austria, a place that was established to promote the legacy of another molester people found impossible to resist, namely Otto Muehl.

There, with the same partner, I mounted one of my favorite exhibitions, and the Paris trip with the Niki de Saint Phalle fountains outside the Pompidou Centre became just a vague memory of that time when I still believed that humiliation and reward went hand-in-hand and that giving form to things had to do with creativity and happiness. It does not. Sometimes it’s just simply all you have left. And maybe the indignities Breillat describes, and de Saint Phalle reconstructs, are symbioses we construct together, either out of boredom or a more deep-seated animosity toward the entire world? I don’t know. The whole time we were in Vienna we smoked DMT in the bathroom at the hotel and consumed inconceivable quantities of Adderall, and it was the last time mama was at any of my exhibitions when she could still walk. On the evening of the opening, the twenty-two year old told me that he just wanted to sleep with someone other than me, and to be honest, I understood him for the first time—I wouldn’t have minded that myself either.

Now, one might ask whether this is so relevant in a text about Niki de Saint Phalle, but on the other hand, what at all is relevant to write about her in 2020? Maybe just a browse through the book Happy would do? I don’t know...

Anecdote: Winter 2020, while I am on a kind of American comeback in Los Angeles after having been known as a meth head who paid for all companionship and came home from the US homeless, I got a call the day before I was to leave from Andrew Richardson, of the magazine and clothing brand Richardson. He asked if I might consider modeling in my new doublet suit with some Beverly Hills Hotel–inspired Richardson towels and hoodies, the same hotel I was staying at.

Vain person that I am, I immediately said yes, and thirty minutes later the photographer arrived and took a series of photos of me while I posed, casually sprawled on a recliner by the pool, with Richardson’s fake Beverly Hills bag. Afterwards I said thank you and was making my merry way through Los Angeles, when I suddenly got a DM on Instagram with a picture of the photographer and another guy with his arms around him.

The text read “Hey king. My king. When can we meet?” I looked at the image and thought, “there is something strangely familiar about him,” and I asked Andrew who the guy was. It was Jack Donoghue from the band Salem. The band that maybe more than any other defined the idea of how one can just be as wasted as possible, do as little as possible and exude sex appeal by, for example, sleeping through interviews with The New York Times, and still have an audience a decade later.

I remember Salem from when I exhibited at Ramiken Crucible in New York, where they played small, unannounced concerts. I must have met him there; didn’t he say he’d had contact with me for some time?

So at fifty-two, and thirty kilos heavier than the time I sat and gawked at the Niki de Saint Phalle fountains all those years ago, the personification of sexy himself wants to meet me. The same “me” that previously identified more with Catherine Breillat’s tortured persona than any other definition of sexy. This time I politely said “no thank you.” Because I knew that back home there was someone who cared about me, and, to put it somewhat unsophisticatedly, neither the book Happy, Niki de Saint Phalle, nor Catherine Breillat could compare with him…

That left me feeling a little Happy.

References

-

Top image: Screenshot